THE Australian Angler changed the face of fishing. I joined the team for issue #4 and stayed on for over 30 years as Fisho, as it became fondly known, morphed from black and white to a full colour Fishing World. When asked to contribute to this print edition [originally published December 2023], three recollections resonated from my body of work.

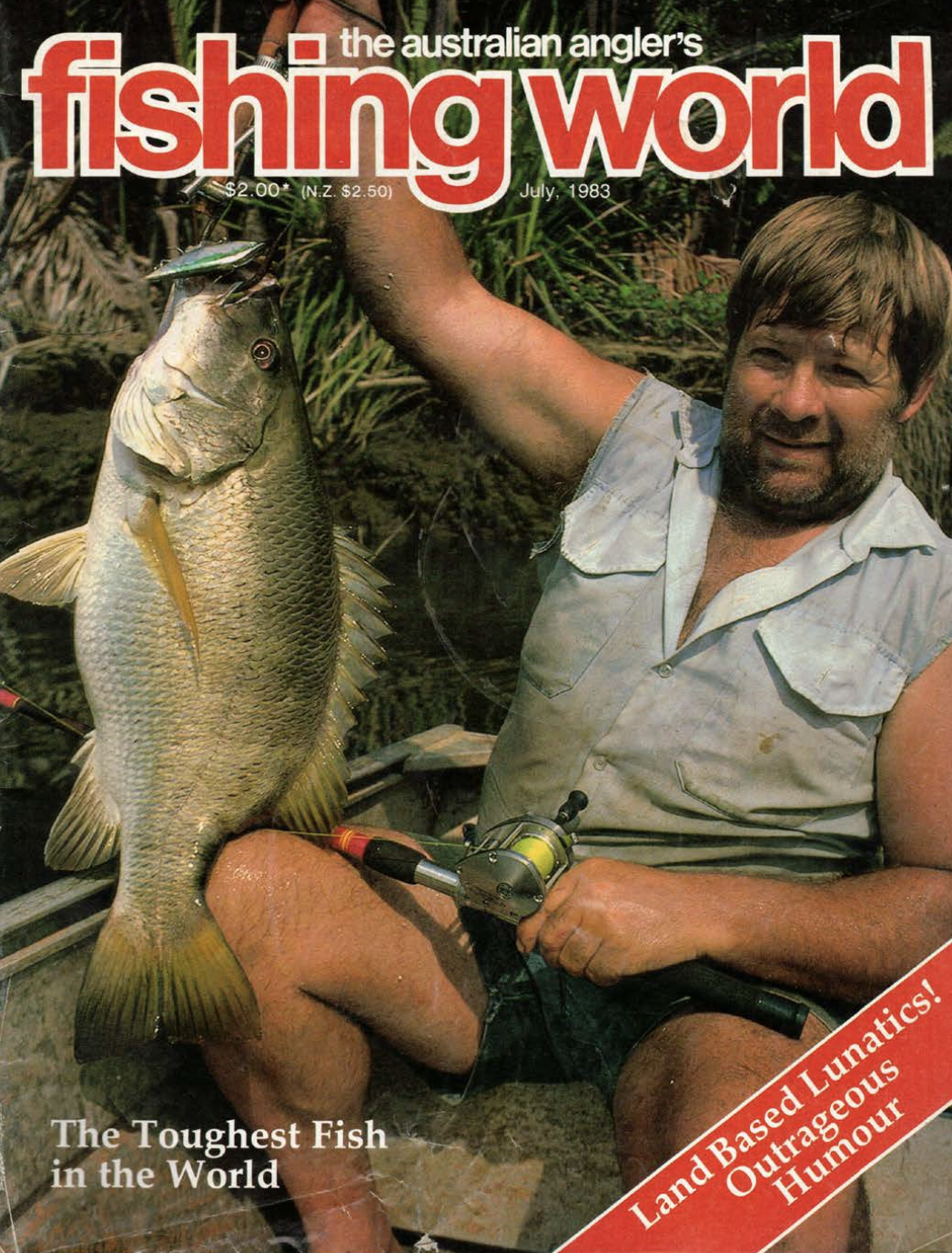

My first feature, an article on the romance of the inland rivers and a unique brand of sportfishing with lures challenged prevailing attitudes and practice. The Cinderella status of Murray cod, golden and silver perch and open slather strip mining rivers with set lines, and worse. The head of Victoria Fisheries no less, on record lamenting Australia’s lack of indigenous freshwater fish of sporting worth. New South Wales counterpart, also blinded by a love affair with trout, going as far as to waste money and manpower on brook trout and Atlantic salmon trials in Copeton Dam.

There was no better time to be introduced to native fish than the years following the 1956 biblical flood. Codfish, it seemed, lay on every snag much bigger than a cricket stump. And yellowbelly were so numerous as to be a nuisance.

“Shake it, boy” he bellowed. I did my best but both hands sometimes weren’t enough for a kid with balls yet to fully drop. Errol reckoned cod came on the bite when woken up. Shaking the bejesus out of a snag was his idea of an alarm clock. On a school holiday adventure I just the right size to ballast the front of the rub-a-dub- dub boat he’d welded from a pair of FJ Holden bonnets. I could swim faster than the contraption of a motor. It began life as a lawn mower then given a mechanical sex-change with a conversion kit Victa also made. It played up a bit and I learned some new swear words. The lures would make today’s artistic craftsman shudder. Blades clipped from a sheep dip tin and mounted on a piece of push bike spoke.

The others checked Errol’s claims at being good at inventing and fixing stuff. All evidence to the contrary, his shearing mater countered; Errol did to everything he touched what Hollywood namesake and legendary pants man did to leading ladies and starlets.

The birds were my job; colourful rosella were plentiful along the river. Murray cod have an un-symbiotic with anything organic and feathered to swim, dive, drinking from a water level snag or decorating a hook. Hanging in the gauzed-in shearer quarter some of the cod fish resembled dressed sheep. Since knowing better, I’m working my way back into the native bird good books the best way I know; popping cats.

By the 1980s overfishing, habitat loss, departmental indifference and a cancer called cotton – not necessarily in that order – brought cod stocks to the brink. The appointment of Dr. Stuart Rowland to head up research happened in the nick of time. In perfecting a hormone injection technique, Dr. Rowland vastly increased hatchery production of native fish fingerlings; however the full potential of the breakthrough was limited by a shortage of brood fish. Gordon Winter, the man linking cod activity with high barometer readings, and I accompanied Stu on brood fish expeditions to Mulwala. The Murray cod Mecca then disfigured by set line springers the hundred cut from inner tube and fastened to trunk and branch with galvanised roofing nails.

Contributing in no small way to the latter day enlightenment appreciation was idiosyncratic Fisho editor Ross Chisholm, convenor of Native Fish Australia. The agitation, dedication and persistence of brilliant yet quirky Will Truman was ere instrumental in saving the upland trout cod and Macquarie perch. But for the likes of fine wool grower Ray Mepham and helpers like Jamie Flett, cod numbers in the New England region would also have nosedived to critical levels. Mepham took it on himself to contour his property to gravity feed a series of brood and grow out ponds. Fingerlings bred in his hatchery were distributed at his cost throughout the region. A monument to this remarkable man stands in Inverell.

By the spring of 1991 fisherfolk and bureaucrat had given up on the Murray. Unseasonal rains that brought down a banker came and went largely unnoticed until Wimmera sheep shearer Rod Mackenzie began writing highly readable, informative and entertaining magazine articles and revealing photographs of his cod catches. The impact was seismic, generous with time and free with his advice, anyone wanting to be someone ended up at his doorstep. More than any anyone or influence, Mackenzie and his body of work can take credit for the kick start revival of Old Man Murray in its spiritual home.

THE RIVER RAMBO

I tried not to act nervous, but in a customs queue and not wanting to be searched. It’s a big call to play it cool when watchful eyes seem everywhere. So far, so good; the sniffer dog ignored the nally bin containing contraband wrapped in a grotty towel with a week’s worth of unwashed jocks.

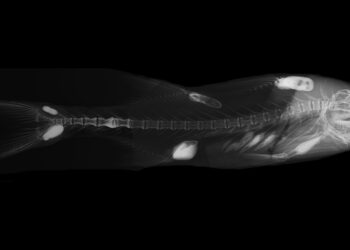

In due course a call came through from Dr. John Paxton, affable Curator of Fishes at the Australian Museum. The good doctor had a match for the specimen I’d delivered. Gathering dust in a backroom, Lutjanus goldeii, a lone and insignificant specimen collected mid 1880s by Australian naturalist Macleay from the Goldie River, a Laloki tributary near Port Moresby. Paxton expressed surprise at the size of the fish in pictures I later sent. The original specimen was provisionally catalogued as a sundry palm-size Lutjanid in the mould of a moses perch.

“Anytime now” Jack Baker muttered. A plume of tannin stained swamp water began intruding into the river, a tide had let go down the estuary.

The ferocious strike happened quicker than the message flashed to the breed the brain. In the same long second as head caught up, line crackled from my reel, headed towards a downstream snag tangle beyond casting distance. I clamped down as the dacron parted like a pistol shot. Ruefully surveying scorched thumbs I’d just lived the most intense moments from a lifetime of fishing.

A glistening yard of barramundi snatched the next retrieve. Good as the experience was, in that context the comparison was that of a parking lot dingle to a freeway hit and run.

I was ready but when it happened the next strike was a jolt with suddenness and kinetics to out-speed reflexes. A presence of mind kicked in, mindful of the impossibility to generate more than 10kilo pressure with a casting rod from a tinny car topper, the best I could manage was to locate the apex of the fighting curve deep in the meaty part to max the pressure output. The fish broke the surface with a defiant tail slap metres short of the snag pile. A judicious relaxing of pressure by shifted rod angles to a higher quadrant brought the bendier tip section into play as a cushion in case of last minute lunges. Spent, in a state of shock with stress bands barring a broad and thick body, it allowed itself to be steered into the net. Downcast pupils eyed the crunched lure between jaws while mine busied noting the resemblance to a mangrove jack though for every pound of the latter I’d been accustomed I’d hooked ten of a big bruiser cousin.

FLY FISHING’S GREATEST

The lone honorific in a genre rich with names and history. My letter was on spec, in essence an invitation… “Dear Lefty, if you’d like to come to Australia I can show you around. You’ll have to rough-it a bit but the fishing will be worthwhile.”

I didn’t think nights under the stars would bother a man spending Christmas in a snow filled foxhole during the Battle of the Bulge but wasn’t expecting a warm four-page handwritten letter.

Off we went; big jets, commuter turbo-props, sea planes, choppers, lodge, yacht and jungle accommodations, thirty days and thirty nights of learning and laughs. Lefty Kreh’s bottomless bag of shortcuts is equaled by a seemingly inexhaustible stream of contagious, side splitting one-liners.

I’d talked-up the black bass as the toughest there were. Lefty nodded but couldn’t hide the twinkle in the eye of a man who’d seen it all

– well, most of it. He cast into the tangled remains of a sunken jungle hardwood….I watched wide-eyed as the shadow detached from cover to skirt wide like a good sheep dog before losing sight… a vicious strike ruptured the leader and left a line burn as if Lefty grabbed a Jedi sword. A re-rig full of shortcuts saw him back in business, and in yet another stunning demonstration of stuff one can’t learn on the casting paddock, the instant the fish struck he wrapped the fly line around the rear of the reel seat…the stop-em-or- pop-em technique in one simple manoeuvre.

Win some, lose some, the then and now of a different world. Where once regarded as heresies, accounts of near seizures as Murray cod detonate on surface lures, and teeth gritting encounters with flyrods bent through to the corks under the impact of lusty golden perch litter the lure and fly lexicon. Gains now assured, the rehabilitated status comes at a cost – No! Make that a loss, the Darling, Australia’s longest the first domino. There will be others, whileever irrigation over-extraction happens and political patronage and attendant corruption keep moving the goal posts.

Forebodings cloud the future for the black bass and spot-tail – a fish I uncovered in New Britain. These acid sportfishing challenges are an own worst enemy, the big ones strike first, sizes reduce exponentially with fishing pressure. And being highly migratory, increased netting decimates schooling bio-masses. However, logging and resultant river siltation loom as the biggest threat to these magnificent fish.

We lost the great man coupla years back. Lefty’s was a full life, simplifying what others still complicate while bringing fly fishing into the 21st century, and touching many along the way. A legacy that lives on.