Much more is now known about the life history of mangrove jacks (Lutjanus argentimaculatus) in Australia today compared to 10-15 years ago. It’s well known (and confirmed by tagging data) that juvenile jacks spend the first few years of their lives frequenting snags and rocky structures in rivers and estuaries until they mature. But once they reach maturity, (usually at between 40 and 50 cm in length), most mangrove jacks move out of the estuaries to offshore reefs where spawning is thought to take place. The eggs and larvae from successful spawning offshore are then transported by currents inshore after which the juveniles return to the estuary to complete the lifecycle. Depending on water temperature and food availability, in tropical northern Australia it has been shown that mangrove jacks usually live for between 4 and 8 years in estuaries before they mature and move offshore. However, on Australia’s east coast relatively little was known until recently about the growth, longevity and movements of this species at the cooler, more southern extent of its range.

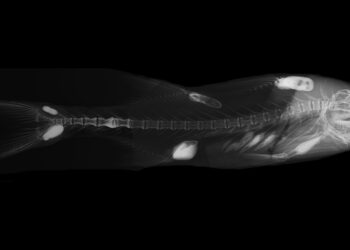

To fill this information gap, a study by researchers in NSW specifically set out to examine the growth of mangrove jacks at the southern end of their range from Fraser Island south to Sydney. The results of the study were published earlier this year in the Journal of Fish Biology and make interesting reading. The researchers found that mangrove jacks in southern estuaries (most of the fish were taken between Port Macquarie and Tweed Heads) grew at least as fast as their northern counterparts, reaching 46-55 cm in fork length in around 6 to 8 years on average, but once they moved offshore they continued to grow to larger sizes than the jacks inhabiting similar offshore environments in Australia’s tropical north. Jacks sampled from estuaries in the study ranged from 19 to 58 cm fork length and were no more than 8 years old, while those captured offshore ranged from 47 cm to a stonker just over a meter long to the tail fork (101cm).

All of the fish caught offshore that were over 70 cm long were also over 20 years of age, but growth became highly variable in the larger fish. For example, the longest meter plus jack was aged at around 52 years old, while the oldest fish in the study was aged at over 57 years old, but was a mere 82.6 cm long. In contrast, another similar sized jack (82.7cm long ) was but pup at only 20 years old. The researchers found little evidence of sex-specific growth with both male and female fish apparently growing at similar rates.

The maximum age of 57 years for the 82.6 cm long jack from northern NSW was actually the oldest reported for any lutjanid, beating the previous record held by a 55 year old red bass (Lutjanus bohar) that was sampled from the Great Barrier Reef. The previous oldest known mangrove jack was a 52 year old fish sampled from northern WA. These results show that once they move to offshore reefs, mangrove jacks, like other tropical lutjanids, tend to have slow growth and live for a long time, suggesting they have low natural mortality rates. This, combined with their relatively large size at maturity, indicates that mangrove jacks are vulnerable to overfishing, especially where they occur at the species “cool-water-range limit”. These results confirm the wisdom of the catch and release activity that most top jack anglers have promoted in recent years. Interestingly, increased growth rates, longevity, and larger maximum size with increased distance from the equator are predicted by the theory of “counter-gradient growth” where fish compensate for shorter summer seasons by growing much faster when conditions are suitable (which assists with winter survival as well). The researchers could not, however, determine with certainty whether mangrove jacks on offshore reefs in northern NSW successfully spawn and contribute to recruitment of younger fish, or whether all jack recruitment in NSW originates from spawning that occurs further north with larvae transported south by the east Australian current.