CHASED by the casual once-a-year angler, as well as the keenest of tournament fishos, bream are arguably Australia’s most popular estuarine “bread and butter” target species. However, our local “bream” are not actually bream at all in the truest sense of the word. The bream name (pronounced “breem”) was originally used to describe freshwater fishes in Europe with narrow, deep sided bodies, such as the common bream Abramis brama (Family Cyprinidae).

In contrast, in this part of the world the word “bream” is pronounced as “brim”, and it is used as a catch-all phrase to describe a variety of species of the genus Acanthopagrus in the Family Sparidae. In fact, there are around 20 species of Acanthopagrus that occur in the Indo-West Pacific region, with no less than 5 of these species found throughout different parts of Australia.

In the southern states the main target species is the black bream Acanthopagrus butcheri. This species occurs in estuaries throughout southern NSW, Victoria, SA, southern WA and Tasmania, grows to around 60 cm and 5 kg, and can live for at least 29 years. Black bream are one of the few Acanthopagrus species that can complete its whole lifecycle within estuaries, and indeed, black bream aren’t found along a large stretch of the Great Australian Bight because of the lack of freshwater in that region.

Arguably our most common species of bream is the yellowfin bream Acanthopagrus australis. This species occurs in estuaries and on surf beaches along the entire east coast from around Cairns in north Queensland to eastern Victoria. In the past this species was recorded to 65 cm long and 5 kg, but a big yellowfin bream for anglers today is around half that historical maximum weight. The southern limit of its range overlaps with the black bream, and the two species have indeed been known to hybridize under certain conditions where yellowfin bream become landlocked together with riverine populations of black bream. As their name suggests, these two species can be distinguished by the colour of their fins – the ventral and anal fins of the yellowfin bream are yellow, but those of the black bream are grey/black.

Further north, a common capture in the tropical estuaries of far north Queensland and the NT is the pikey bream (Acanthopagrus pacificus). This species grows to around 3 kg in weight and differs from the yellowfin bream by having darker, black/grey body and fins, as well as much stouter dorsal and anal spines. The western cousin of the pikey bream is the northwest black bream (Acanthopagrus palmaris), which occurs throughout northern Western Australia from the WA/NT border south to around Geraldton. Both pikey bream and the northwest black bream are very similar in appearance (all grey fins and strong spines), grow to similar sizes and are quite difficult to tell apart except for some differences in their head profiles (which aren’t really apparent unless you have both species on hand at the same time). But if you’ve caught a bream without yellow fins in northern WA, chances are you’ve caught a northwest black bream, while if you’re in the NT or north QLD, its most likely a pikey bream.

The most recently recognised Aussie bream is the western yellowfin bream (Acanthopagrus morrisoni). This species was described only around 10 years ago, namely because it differs from all other species of Australian bream by having not only yellow pelvic and anal fins, but also a yellowish tail (with a black margin on the trailing edge). It occurs only in tropical Australia from around Geraldton in WA north throughout the Kimberly, NT and Gulf of Carpentaria in north Queensland. The western yellowfin bream remained incognito for so long because previously, it was thought to be another species of bream (Acanthopagrus latus), but scientific investigations found the latter was restricted in distribution only to Japan, Taiwan and Vietnam.

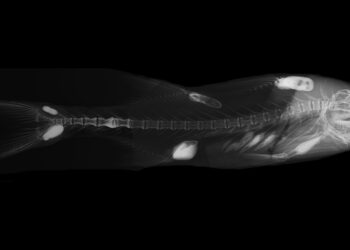

With members of the genus Acanthopagrus all being relatively large and tasty species of importance to commercial, recreational and artisanal fisheries, it is amazing that new species of bream are still being found. Yet this is exactly what happened more recently in the Red Sea, when members of the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST) in Saudi Arabia found a new species of bream in early 2021. What’s more, the new species was captured by university staff who were recreationally fishing! Compared to the other local Red Sea breams (which included the goldsilk sea bream Acanthopagrus berda, and the strikingly gorgeous double-bar sea bream Acanthopagrus bifasciatus), the “new bream” had a different head profile, paler body color, a more yellowish pectoral fin and a distinctive black patch on the rear edge of the operculum. These differences prompted an investigation, and the rest is now history as the fish was eventually described as Bev Bradley’s Bream (Acanthopagrus oconnorae) (named in honour of the discoverer’s wife and mother).

Given that this relatively large (up to c. 30 cm long) fish had eluded scientific identification for around 250 years, its discoverers suspected that the reason why might be that it favours shallow water in and around mangroves, which are areas not regularly targeted by commercial fishers (nor scientific fishers or divers). Fascinating stuff indeed. For more information on the new bream species, check out the study at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/jfb.15147

And the background story at: https://insight.kaust.edu.sa/2022/05/11/the-tale-of-bev-bradleys-bream-and-the-vprs-fish-supper/

Figure 1. A and B show examples of the newly described Bev Bradley’s Bream