BACK in March 2002 I wrote a Fish Facts column that explored the known biology of spangled emperor (Lethrinus nebulosus) at that time. The column concluded: “Considering their undoubted importance to our northern fisheries, its surprising that so little is known about the life history of spangled emperor in Australian waters.” Since then there have been several studies that have filled in many of the gaps.

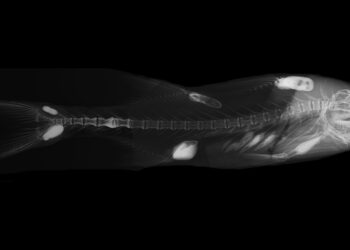

Otherwise known as yellow sweetlip or north-west snapper, spangled emperor are one of the largest emperors of the family Lethrinidae, growing to over 80cm and in excess of 7kg. Adult spanglies inhabit coastal and offshore reefs, where they are particularly common over coral rubble and sandy areas in coral reef lagoons, while juveniles can be found both in these places and also in inshore mangrove and seagrass nursery areas. This species can be encountered throughout Australia’s warmer waters north of Sydney and Perth, particularly around coral reef areas. They are also found throughout the Indo-Pacific as far east as the Cook Islands, as far north as Japan, and as far west as the Red Sea and Madagascar.

The larger spangled emperor can be quite old, with 70cm fish being aged at 10 to 30 years. Back in 2002 it was not clear whether spangled emperor actually changed sex from female to male, as other lethrinids are known to do, or whether the sexes remained separate. Recent work by researchers in Western Australia has now confirmed that its really a bit of both. In WA all immature L. nebulosus had non-functioning female gonads, then at around 28cm long (2 to 3 years old) some changed sex to male and became reproductively active, while the remainder stayed as immature females until they began maturing one or two years later (50 per cent of females matured by 39cm at 3 to 5 years of age). This reproductive strategy is known as a non-functional protogynus hermaphrodite, which is basically identical to having separate sexes (functional gonochorism).

Because spangled emperor are so widely distributed, it is interesting to compare the data for age at maturity in WA compared to other regions in the middle east and Asia, where the same species is found to mature at much lower sizes, for example, around 20cm and a maximum recorded age of 11 years in the southern Arabian Gulf.

The authors of the Arabian Gulf papers rationalised their findings by stating they were probably due to heavy fishing in the absence of a minimum size. In WA, all of the immature male spangled emperor and over 50 per cent of the immature females were protected by a 41cm minimum size, which, the authors of the WA paper concluded, meant that the minimum legal size was effective for preventing recreational fishers retaining at least half of the juvenile males and females in their landed catches. WA researchers also found evidence that spangled emperor stocks in WA were healthy in the South Gasgoyne region, but were showing early signs of overfishing in the North Gasgoyne region (which contains Ningaloo Marine park, with 30 per cent fishing closures). To me, it appears that fish stocks outside the green zone closures in the marine park may have been adversely affected by fishing being concentrated into the smaller area that remained open.