IT is now established that sharks have well and truly joined the “charismatic marine megafauna” club, previously occupied only by whales, dolphins and turtles. As a consequence, they have attained what certain environmental groups consider to be mythical powers. I have opined previously that perhaps these mythical powers arise from their starring roles in such esteemed documentaries as Finding Nemo, where the shark characters were “reforming” and consumed no other fishes for the duration of the movie. Reality is of course, very different, and in the real world sharks tend to be highly predatory on other fishes, and often themselves as well. Nevertheless, when the prickly problem of shark depredation in commercial or recreational fisheries arises, environmental groups are quick to declare that sharks are able to do no wrong.

What is shark depredation? What anglers commonly refer to as “shark tax” has been defined as “where a shark partially or completely consumes an animal caught by fishing gear before it can be retrieved to the fishing vessel”. This tends to separate depredation from situations where fish may be consumed by sharks after being released, which is known as “post-release predation” or “facilitated predation”. Depredation can occur not only in hook and line fisheries, but also net and trap fisheries, and studies have shown it can be a source of significant (up to 26%) “hidden mortality” in those fisheries affected.

In the past, I always thought that a shark must naturally eat lots of other fish to survive and grow to a large size, and thus when they eat “our” fish by taking them from our fishing gear, fishers were simply witnessing a natural event that occurs out of sight, out of mind countless times every day worldwide. However, today it seems that the modern trend is for shark depredation to be seen as an emerging “human-wildlife conflict”. This change in perception from experience to conflict fits with the modern urbanised/westernised view of the Anthropocene world that dictates fishers are no longer a natural part of the environment (note: beware, this way of thinking also leads to a conclusion that fishing is no longer a natural thing for people to do).

Today, human-wildlife interactions are under the research microscope in many recreational fisheries, with examples including not only depredation by the “grey coated tax man” in fisheries worldwide, but also depredation by other species too, such as large groupers, seals and dolphins.

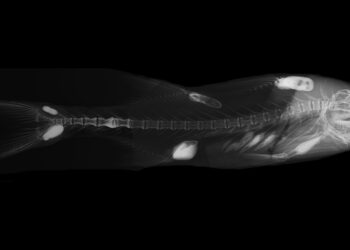

Indeed, some researchers are concerned that human–wildlife conflict will continue to increase in the future due to shark depredation, and that other problems may also arise, such as “the possibility that sharks may bite and injure each other whilst competing to depredate hooked fish”. Such a concern arose after some researchers working in the Seychelles with drumlines reported a process of “cumulative depredation”, where a 1 meter grey reef shark was consumed by a 2 meter bull shark, which in turn was then itself depredated by a much larger (c. 4 meters) tiger shark. The fact that sharks are cannibalistic and in nature will eat other sharks when given the chance is well known and has been occurring for millions of years, however once fishing gear is involved with the process, it is considered as a problematic human–wildlife conflict.

Certainly, depredation is an extension of natural feeding behaviour where sharks prey on injured or unhealthy fish. There are, however, some legitimate concerns. If the amount of fishing gear in the worlds oceans is not controlled, populations of target fish species may be impacted, as the overall “fishing related mortality” associated with the gear deployed will likely be higher in fisheries where significant depredation occurs. The concern of researchers is that the extra “shark tax” mortality will be hidden and not recorded in commercial fisheries logbooks or accounted for by measures such as recreational daily bag limits.

Other researchers observe that depredating a hooked fish is unnaturally beneficial to sharks because it is more energy efficient compared to locating, capturing and consuming untethered prey. Depredation also alters energy flow in systems where sharks are enabled to feed on fish species that they might not normally feed on, perhaps because they are usually too large or fast for the sharks to capture in their natural environment. Certainly, the sounds and vibrations of fish struggling on a line or after being speared has been scientifically proven to be highly attractive to predatory sharks including bull sharks, Galapagos whalers, blacktip and whitetip reef sharks, thresher sharks, blue sharks as well as makos. But research also shows that sharks can quickly habituate and become attracted towards the sounds of boat engines, echosounders or anchor chains over long distances, certainly over several hundred meters and possibly even further. The habituation is strongest when the sharks become used to the presence of fishing boats, are not themselves being caught, and begin to associate the engine and echosounder noise with the availability of easy prey.

This, combined with the reduction in directed fishing pressure on sharks in Australia in recent years (due to increasing restrictions on commercial fishing, and the fact that most Aussie recreational fishos release the vast majority of sharks they interact with) provides a surprising upshot. The higher the fishing pressure in a given area, the more likely you are to experience shark depredation. This has been shown in studies in Ningaloo Marine Park in WA where researchers found that the time required for lemon sharks to approach a baited camera in deployments over 6 consecutive days was quickly reduced when the camera was placed in an area that received regular fishing pressure, whereas in no-take sanctuary zones, very few sharks were attracted using the same method (which also says something about potential artifactual behavioural problems when researching sharks in green zones). Another study at Ningaloo found that depredation by sharks occurred on around 40% of recreational fishing trips, taking on average around 11-13% of all fish caught, with higher depredation occurring in areas which received greater fishing pressure. These results confirmed that if fishing is not removing sharks, depredation rates tend to increase due to behavioural association by the sharks, which rapidly learn to associate recreational fishing activities with a food reward.

Similarly, scary associations have been recorded elsewhere, such as the acoustic tracking studies of large bull sharks in the Breede Estuary in South Africa, which showed these fish tended to remain near recreational fishing vessels, even following them for short distances when they moved spots.

So, what can be done about it? Researchers recommend regular movement between fishing spots to reduce the chance of sharks locating a fishing vessel in the first place, and relocating to another fishing spot after a fish is depredated. Use of fewer hooks (e.g. single instead of multiple hooks on each line to avoid having multiple fish struggling on the line at once), and avoidance of use of burley are also recommended, as is use of stronger fishing line to allow faster landing of the fish. Of course, there is also the option to fish down the shark populations, but remember, they are now charismatic!